Due to an unfortunate hardware failure and some supply chain logistics issues, I recently found myself stuck using a Chromebook for the next month. A majority of the work that I do in the office (answering email, editing docs, making slides, etc.) was not a problem, and I really didn’t notice much of a difference.

But then, someone asked me for a code snippet, and I froze. I searched for a text editor (Sublime, Atom, Vim, anything really…), before realizing that not only did my Chromebook not come with an editor, I couldn’t install one (at least, not in the traditional sense of the word).

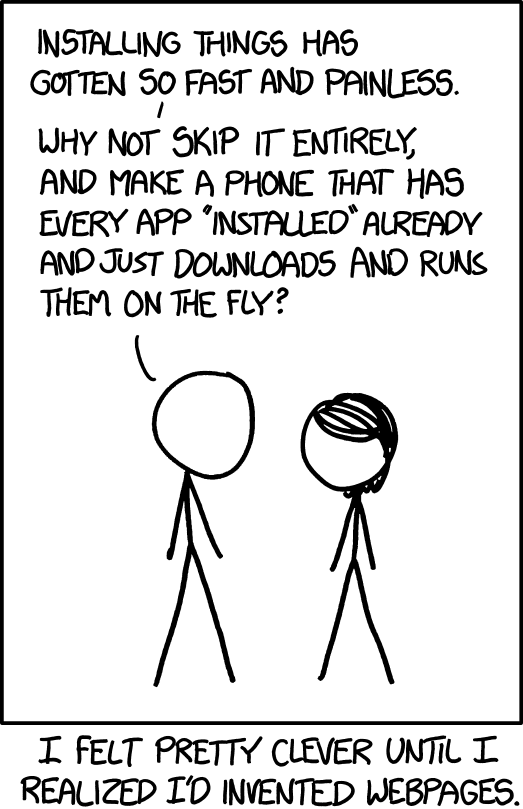

That’s when I finally understood the point ChromeOS is trying to make:

When using a Chromebook, it’s assumed that you’ll always have connectivity, and that all the services you want are available in your browser. For the general case of, “being in a school or office using online SaaS offerings,” this makes perfect sense. Even better is that since the machine requires next to no configuration, hardware is easily swappable between users, and there’s no need for explicit ownership.

However, when it comes to development work, where toolchains are highly customized and often platform specific, and local development is king, I wasn’t sure how well this model would work. Being stuck with this machine for a month, I wanted to find out how well suited Chromebooks are to a power user workflow.

Testing my hypothesis

I devised an experiment to answer this question: could I write and publish an entire blog post using only my Chromebook? A few quick searches gave me the following options:

- ChromeOS development mode and crosh

- Install a new OS via Crouton

- SaaS IDE (Cloud9, Orion, etc.)

- SSH into a VM ([SecureShell(https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/secure-shell/pnhechapfaindjhompbnflcldabbghjo?hl=en)] + GCE/EC2 instance)

My first task was getting a shell working, so I could install software, get SSH keys, etc. crosh is the ChromeOS shell, but is only really usable in “Developer Mode.” I’ve rooted (and broken) enough Android devices, but since this was a loaner laptop, I didn’t want to return it in a signficiantly altered state. I also worried that even if I got into crosh, none of the software I wanted would work.

Using a tool like crouton, which installs another OS, was a viable alternitive, but going this route felt like it violated the principle of my experiment. The goal was to test ChromeOS and it’s cloud first model, so it felt like cheating to install Linux and claim “I did this all on a Chromebook.”

The next option was to use an online editor like Cloud9 or Orion. I’d used Cloud9 before (it’s the default editor on the Beaglebone), so I started down that path. Until I hit a paywall.

If you know anything about me, you’ll know that I’m a huge proponent of SaaS (really any *aaS product), but I also hate paywalls, especially for free trials. The product manager and paranoid SRE in my understands why paywalls (accountability), but as a consumer, I still find them hard to swallow.

Since I’ve already put money into the public cloud, I decided that I might as well learn how to build my own environment on raw infrastructure and build my own SaaS IDE.

Building an environment

Luckily, I didn’t have to travel too far. Cloud9 provides their editor as open source software (how the Beaglebone runs it), which I was able to spin up pretty easily on a Compute Engine VM (f1 micro, preemptable). With an estimated monthly cost of $2.65, it felt close enough to free that it was worth trying out.

After creation, I immediately SSHed in and set up Cloud9:

# Install Nodejs and other deps

sudo apt-get install python-software-properties build-essential

curl -sL https://deb.nodesource.com/setup_7.x | sudo -E bash -

sudo apt-get install nodejs

# Install Cloud9

git clone https://github.com/c9/core.git c9sdk

cd c9sdk && ./scripts/install-sdk.sh

# Install foreverjs and start the server

npm install -g forever

forever start server.js \

-p PORT \

-l 0.0.0.0 \

-a username:password # pick something other than these ;)

I also had to add a Network Firewall Rule to allow traffic on my port. I did it via the Cloud console, but you can also use the CLI:

gcloud compute firewall-rule create cloud9 \

--allow=PORT \

--source-ranges=0.0.0.0/0

Next steps

There are a few obvious issues with the current setup:

- Typing in a IP address and port isn’t the best experience

- Traffic should be HTTPS

- Login credentials shouldn’t hard coded in the startup process

The solution to the first is easy: buy a domain and point DNS at the VM’s IP.

The solution to the second is a little more involved: create a cert from Letsencrypt and use nginx or Google Cloud Load Balancing to terminate SSL. Honestly, given the number of connections anticipated (1), setting up load balancing seems like overkill, so I’m probably just going to use nginx. Certbot makes this easy to set up, and also automates cert renewal.

The solution to the third comes courtesy of a coworker recommendation: put an OAuth proxy in front of all traffic. Bitly offers an open source OAuth proxy that conveniently has an example on how to set it up with nginx.

These are all things that any SaaS IDE must have, and if I want this to be

anything more than a toy, I’ll have to do them soon. But for now, I need to get

this post published, so I’ll leave those as a TODO.

First impressions

While online, I was pleasantly surprised how well this model worked. The IDE was on par with Atom and Sublime, the terminal snappy, and the overall experience was very smooth. The concept of “apps as browser tabs” is still a little foreign to me, especially when trying to switch from my IDE to docs and getting lost in the sea of browser tabs already open, but I don’t think this is a dealbreaker.

Offline mode is a whole other story. I had a quick flight from SFO to SEA, during which none of the standard GSuite apps worked (though I was able to edit notes stored in Keep). I fully expected my cloud based editor to fail, but surprisingly the editor and JS REPL seemed to work, even when the command prompt and file system didn’t work. It wasn’t unti after I landed that I realized the first draft of this blog post didn’t get saved, and when my VM was preempted, I ended up losing it.

I’ve only been at this for about a week, so I can’t say for sure if this will be a great fit for my development style, but so far it seems to be “passible but not ideal.”

#thefuture?

A number of companies have already explored the idea of employees not having their own desks (see “hot desking”), so employees not owning their own computers seems like a logical next step for organizations where space and hardware are at a premium. The Chromebook makes this future possible, since anyone can log into a Chromebook and have adding personalized experience, so long as you rely solely on online SaaS offerings to get your job done.

Making it possible for software professionals (and others with local toolchains) is going to be much harder. Chrome Apps seem to be an option here, but they just don’t seem to have the same traction that other platforms are having. Ideally the success of Progressive Web Apps (the mobile analogue) will make the Chrome App development experience better. Even more ideally, PWAs could be automatically built for mobile and ChromeOS, and things would Just Work™.

When I can type “text editor” into the Chromebook search bar and open my editor and build software, online or off, I’ll know we’re finally getting close. Until then, I’ll keep waiting for my new Macbook…