Several years ago, on my first work trip to New York City, I happened upon Booker and Dax, a cocktail bar run by Dave Arnold. While there, I had one of his famous perfectly clear Gin & Tonics, as well as several other weird and wacky cocktails. Unfortunately, the bar closed down a year or two after I visited, but I was ecstatic when he published Liquid Intelligence, a scientific approach to making great cocktails. This book led me to Modernist, where Carlo would make Aviation infused grapes, smoked Old Fashioneds, and more. I was entranced.

There have been numerous reports of alcohol consumption increasing by 40-50% during quarantine, and I am no exception. However, in an effort to make my increased consumption educational, I’ve been experimenting with various styles of cocktails as well as different flavors. Safety, fun, and learning, in that order. While I was pining away for a canned whisky highball one hot afternoon, I realized that I could fairly easily mix whisky with soda water and force carbonate it in an iSi whipper. Pulling my copy of Liquid Intelligence off the shelf (is this what life before the internet was like?) I flipped to page 312 and started reading about what I needed to do. This led to several experiments, me re-reading a large portion of the book, and buying a full carbonation rig (5lb CO2 tank, regulator, etc.).

The Fundamental Theorem of Cocktails

When I re-read the book, I was reminded of Dave’s grand unifying theory of cocktails:

for any given cocktail structure (e.g. shaken, stirred, carbonated), a “good” cocktail

would have a certain amount of alcohol, sugar, and acid. In typical fashion, he quantified

all of these (pg 125-126), provided formulas for dilution (pg 123), and listed the ABV, sugar

content, and acid in common ingredients (pg 136-137). Everything was well defined and waiting

for a tool to allow me to adjust ratios on the fly and calculate the perfect cocktail.

Dave has a few recipes for carbonated drinks in his book, but of course I wanted to gather additional resources. I stumbled upon cocktailgeni.us, where Matt has a number of recipes for carbonated cocktails (like a Paloma), among other interested recipes building on what Dave provided.

Turns out Matt also runs CocktailCalc, a website that implements Dave’s formulas to give you the proper ratios for cocktails of a certain structure. He also provides recipes and full information to members of the website. I took one look at the website and said “I can make one of these,” (usually a fallacy–buy, don’t build!) and immediately set about the best way to create a tool for me to craft the perfect carbonated cocktails.

Spreadsheets to the rescue

While the entirety of CocktailCalc is client-side, I had little desire to copy it. I also had little desire to fight with web frameworks for hours to build a passable UI, when all I really cared about was a tool I could adjust on the fly.

I had spent the earlier part of the work day building a simple model to approximate traffic and revenue based off of customer growth in a spreadsheet, which was a huge hit with the engineering team. They could play around with my assumptions, model their own growth, and immediately see the consequences.

Beautiful, beautiful spreadsheets

I remember the first time I saw a spreadsheet that took my breath away. Freshman year of college, we had to design and build a processor on an FPGA. We’d done all the architecture, written our custom assembly code, and were ready to load it into memory–except we had no idea what to load. One of my teammates casually opens his laptop and pulls up an Excel spreadsheet containing a full blown assembler for our assembly, puts our instructions in, and out pops a memory map we can load on our FPGA.

Mind.

Blown.

My college girlfriend’s dad was a financial planner, and my graduation gift was an entire financial plan in Excel, complete with AMT calculations, all the fancy retirement savings vehicles, and more. I still use it years later because its easy to modify and can give me a very accurate picture of what things look like. Not perfect, but it doesn’t have to be: all models need to do is be accurate enough to help you make decisions quickly.

More recently, the original CovidActNow model was a spreadsheet, and it allowed for extremely rapid iteration as well as introspection into the model.

And finally, my interpretation of Dave Arnold’s grand unified theory, in spreadsheet form.

Why spreadsheets?

I believe spreadsheets have a several fundamental properties that make them so great: they are easy to understand by nearly anyone, straightforward to modify, and trivial to share.

1. Spreadsheets require no knowledge of programming

Spreadsheets are the most common programming language currently available, and nearly anyone can look at a spreadsheet and quickly understand what’s happening. If you don’t, double click on a value and you can see how it’s calculated! The formula is right there! All “variables” point to the cells the data is coming from, so your debugger is built right in.

And if you have knowledge of programming, you can augment your spreadsheets with VB or AppScript.

2. Spreadsheets are easily modifiable

A good spreadsheet model pulls all assumptions and inputs into clearly defined places where you can modify one value and let the model cascade from there. Again, no CS degree required to make changes, just the ability to highlight a cell and change it’s value or edit a simple formula to be slightly different.

Print statement debugging is as easy as copying the formula into another cell and tweaking whatever you need. The feedback loop is incredibly tight and allows for an iteration experience that’s unparalleled (I’m sure folks will argue that XCode Playgrounds, JuPyter notebooks, and Lighttable do this).

3. Spreadsheets can be shared and accessed by anyone, anywhere

Lastly spreadsheet applications are as common as web browsers (not only because every browser can also be a spreadsheet), and the format is interoperable. Anyone can grab your sheet and view it, modify it, and share it. Spreadsheets are arguably even better because they almost always run offline (so all the road warriors can use them on planes) and they can be transferred via offline only mediums–good luck downloading a website and running it offline!

What’s wrong with sheets?

This post is already pretty long, so I’ll save this for a second post where I talk about tips and tricks for sheets, but ultimately I think there are two main problems inherent in spreadsheets that make them difficult to use more broadly (or to replace tools like CocktailCalc): because they are so easy to share and modify, they are extremely difficult to secure and monetize.

Testing the sheets

Ok, enough of the boring part, let’s drink!

I knew I wanted to write a blog post on spreadsheets and cocktails, but was stuck on the name. I went for a run, and two miles in, the name came to me. I realized that I had to make several variations of the namesake cocktail, so I stopped by the bar on the way back and got a few ounces of white rum and cheap cognac to test the recipes out, using the spreadsheet for guidance.

Here’s what I found out.

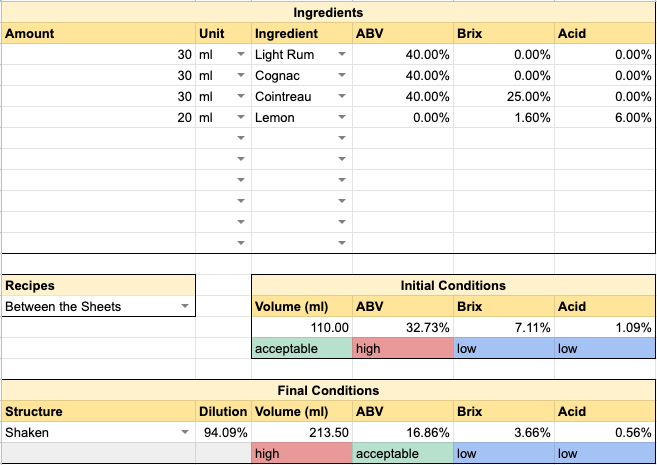

IBA recipe

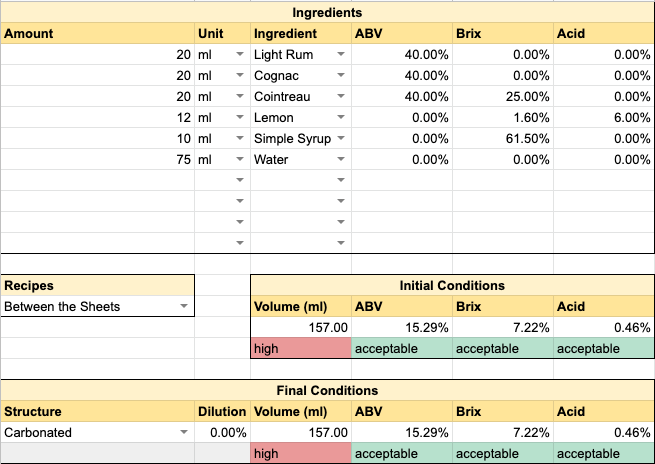

The IBA recipe for a Between the Sheets comes in… lacking.

The drink is low in both sugar and acid, so it’s likely going to come out tasting rather thin. And indeed, when making it, it came out pretty watery and not like a proper cocktail. If I got served this in a bar, I probably would have sent it back. The only thing it has going for it is that the recipe is pretty straightforward.

I calculated the dilution for this drink and came up with roughly 58%, which is a ways away from the 90+% predicted by the model. Unsure if my ice is different sized and thus that’s changing things, or something else is at play. Liquid Intelligence claims that a shaken cocktail should have 50-60% dilution (pg 125), so the drink is right and my calculation is clearly wrong.

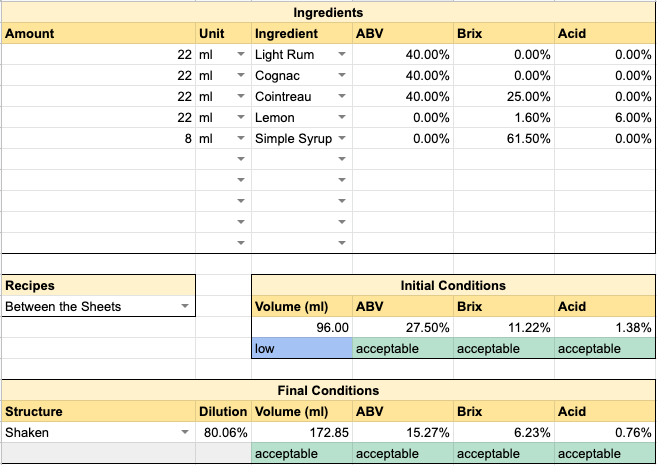

My modified recipe

The drink needed more sugar and more acid, so I tweaked the ratios a bit to get a more balanced drink.

Because Dave Arnold is a wizard and the FTC works, this version is much better. It tastes less watered down and generally more balanced. Honestly, it’s pretty amazing to watch this tool work its magic.

Dilution came in at 42%, which again is lower than calculated (and below the low end of the range published in Liquid Intelligence), though in roughly the correct difference for the difference in ABV.

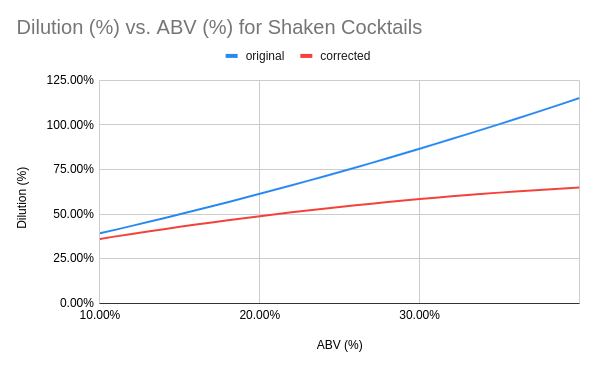

After playing around with the equation, I believe Dave forgot the - sign in

the shaken cocktail dilution equation (pg 123), which should instead be:

-1.567 * ABV^2 + 1.742 * ABV + 0.0203. That results in 50-60% dilution for

the ranges of ABV we’re likely to see, and seems more consistent. I have fixed

this in my calculator, so it should be correct.

This was pretty easy to verify. Again, chalk one up for sheets ease of use:

A quick re-run of the calculations shows that I’m still right about the first one being weak (you can’t recover from too little starting sugar and acid), and the second one being about right.

My carbonated recipe

The carbonated version was fairly easy to adapt: just add more water and reduce the acid.

If you’re Dave Arnold, you’ll clarify the lemon juice and Chitosan/Gellan wash the Cognac; for everyone else, strain the lemon juice through a fine mesh strainer (and add it afterwards) and don’t use the 20yo cognac, it’ll be fine.

Honestly, I like the carbonated version the best. It’s a much more refreshing version of the above cocktail, plus, since the dilution calculations above don’t matter, so you can really dial in the profile you want. Maybe that’s why I liked it better…

If you liked this post, feel free to share on the internet, or let me know what cocktail I should carbonate next!